"Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown" in the collection of essays The Captain's Death Bed by Virginia Woolf (Hogarth Press, 1950) 224 pages

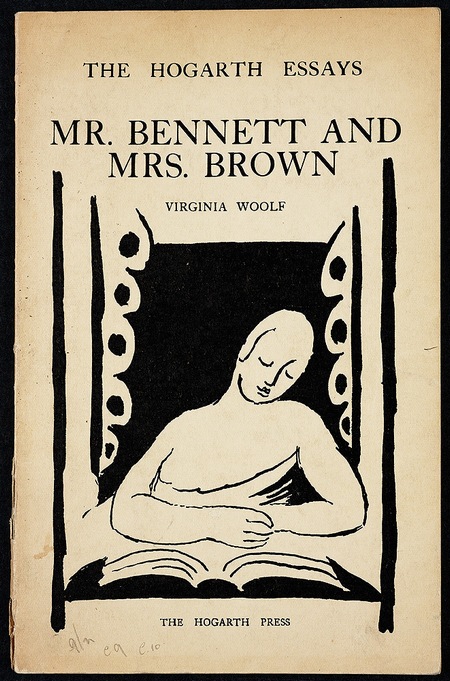

A few months ago I picked up a collection of Virgina Woolf's essays compiled in The Captain's Death Bed at a St. Michael's College book sale. The jewel in the crown was an essay on modern fiction called "Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown". As you can see it was also printed separately by the Hogarth Press (as seen to the left).

Woolf begins with the image of a writer trying to capture a sort of phantom "Some Brown, Smith or Jones" who urges her to "Catch me if you can ..." That phantom is "character".

Few catch the phantom; most have to be content with a scrap of her dress or a wisp of her hair.

In support of this, she cites the writer Arnold Bennett who agrees that, "The foundation of good fiction is character-creating and nothing else." and then goes on to proclaim that there are "no young novelists of first rate importance at the present moment ..." [This paper was delivered to the Heretics at Cambridge University on May 18, 1924]

|

| Eliot |

Woolf reflects on this and feels that she must divide English novelists into two camps: the "Edwardians" (H.G. Wells, Arnold Bennett and John Galsworthy) and the "Georgians" (E.M. Forster, D.H. Lawrence, Lytton Strachey, James Joyce and T.S. Eliot). She could easily have included herself but does not. The latter group were, and still are, modern and, to various degrees, genre shattering, revolutionary in their fields. As an example of the importance of character, Woolf cites how a "character" has captivated her. She explains how she spied an older woman on the train from Waterloo to Richmond, a "Mrs. Brown" as she so names her, who is accompanied by a middle aged man, who, Woolf, surmises, is somehow menacing the woman, not physically but psychologically. "There is something pinched about her - a look of suffering, of apprehension ..." Mrs. Brown is "very clean, very small, rather queer, and suffering intensely".

A fictional scenario ensues in Woolf's mind (by the end of the essay we are still not sure if a "Mrs. Brown" truly existed): Mrs. Brown is a widow with an only son; she is extremely impoverished but comes from "good" stock; they were once so exalted that her grandmother had a maid. The younger man, "Mr. Smith", is "bigger, burlier, less refined. He is a man of business and he had some "power over her which he was exerting disagreeably ..." At one point, she cries and the man ignores her as if he has seen this many times before. Why does Woolf present this scenario?

What I want you to see is this. Here is a character imposing itself upon another person. Here is Mrs. Brown making someone begin almost automatically to write a novel about her. I believe all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite.

Character is what we take away from the great books she argues (as does Arnold Bennett). War and Peace, Pride and Prejudice, Vanity Fair, Madame Bovary ... The lovers Natasha and Pierre, the inestimable Elizabeth Bennett, the shrewd Becky Sharpe, the doomed Emma Bovary. But Bennett sees no great characters in the writings of the "Georgian" (read "Modern") writers. Woolf demurs. The Edwardians, she asserts, do not see Mrs. Brown.

The Edwardians excelled at describing the "fabric of things". Woolf cites a book written by Bennett called Hilda Lessways and how Bennett opens the books with an intricate description of the home in which she resides, the neighborhood, who resided where, the architecture, the town, the weather. And so, Woolf complains, we cannot hear Hilda's voice "only Mr. Bennett's voice telling us facts about rents and freeholds and copyholds and fines". These restrictions, these limitations, have had a certain effect on modern writers. ... the feeble are tempted to outrage. and the strong are led to destroy the very foundations and rules of literary society.

I love the analogy she cites of a teenage boy staying with his aunt for the weekend who in desperation "rolls in the geranium bed as the solemnities of the sabbath wear on". The modern writer is bored, tired of the same conventions, restless, destructive. They are, she says, sincere, desperate, courageous and it is only that "they do not know which to use, a fork or their fingers".

The interior life of characters is largely absent; hence, her discomfort with the old ways of doing things.

|

| Joyce |

But she does not overly praise the moderns. Joyce is "indecent", Eliot "obscure". Joyce's indecency in Ulysses seems "the conscious and calculated indecency of a desperate man who feels that in order to breather he must break the windows". When the window is broken he is magnificent but "what a waste of energy!" she exclaims.

Eliot has written some of "the loveliest single lines in poetry". But:

... As I sun myself upon the intense and ravishing beauty of one of his lines, and reflect that I must make a dizzy and dangerous leap to the next ... like an acrobat flying precariously from bar to bar, I cry out, I confess, for the old decorums ...

And is she not right? As much as they thrill, these modern writers also disorient, at times even bore with the stridency of their inventions, do they not? They represent an alluring "season of failures and fragments".

What is the readers' obligation here? To insist that writers describe "beautifully if possible, truthfully at any rate." We must tolerate the "spasmodic, the obscure, the fragmentary, the failure" for we are "trembling on the verge of one of the great ages of English literature".

As always milady, your arrow hits the mark. For who do we read? Whom do we turn to for truth, for beauty today? For the most part it is not Wells, Bennett or Galsworthy but Forster, Lawrence, Joyce, Eliot and of course ... Woolf.

No comments:

Post a Comment