Anthony De Sa was born in 1966 and grew up in Toronto’s fledgling Portuguese community. His short fiction has been published in several international literary magazines. Barnacle Love is Anthony's first book and has garnered critical acclaim across Canada and the U.S.A. Barnacle love was a finalist for Canada’s most prestigious Scotiabank Giller Prize and a finalist for The Toronto Book Award. His novel in progress, Carnival of Desire, will be set in 1977, the year a twelve-year-old shoeshine boy named Emanuel Jaques was brutally raped and murdered in Toronto. Anthony lives in Toronto with his wife and three boys.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

April is the cruelest month...

Anthony De Sa was born in 1966 and grew up in Toronto’s fledgling Portuguese community. His short fiction has been published in several international literary magazines. Barnacle Love is Anthony's first book and has garnered critical acclaim across Canada and the U.S.A. Barnacle love was a finalist for Canada’s most prestigious Scotiabank Giller Prize and a finalist for The Toronto Book Award. His novel in progress, Carnival of Desire, will be set in 1977, the year a twelve-year-old shoeshine boy named Emanuel Jaques was brutally raped and murdered in Toronto. Anthony lives in Toronto with his wife and three boys.

Maria Meindl’s essays and fiction have appeared in journals including The Literary Review of Canada, Descant and Musicworks. She has made two series for CBC Radio’s Ideas: Parent Care, and Remembering Polio. She has two publications coming up soon: Outside the Box: the Life and Legacy of Writer Mona Gould, the Grandmother I Thought I Knew from McGill Queens University Press, and a story “The Last Judgment” from Found Press. http://www.bodylanguagejournal.wordpress.com/

Sheila Murray’s short fiction has been published in Descant, The Dalhousie Review, Exile, and is forthcoming in the Diaspora Dialogues anthology, TOK: Writing the New City. She has completed a collection of short stories, Upside Down, and a novel, Edward, supported by the Toronto Arts Council. Based in Toronto, Sheila writes about immigration and is a documentary filmmaker and sound editor.

Elana Wolff has taught English as a Second Language at York University and at The Hebrew University in Jerusalem. She currently divides her time between writing, editing, and facilitating therapeutic community art. Elana's poems have appeared in journals and anthologies in Canada, the US, and the UK and her third collection, You Speak to Me in Trees (Guernica, 2006), was awarded the 2008 F.G. Bressani Prize for Poetry. Her most recent book, Implicate Me (Guernica, 2010), is a collection of short essays on individual poems by Toronto-area poets; a new book of poems, Startled Night, is forthcoming this fall.

And as emcee...

Michelle Alfano is a co-organizer of the (Not So) Nice Italian Girls & Friends Reading Series and a Co-Editor with Descant. Her novella Made Up of Arias (Blaurock Press) won the 2010 Bressani Prize for Short Fiction. Her short story “Opera”, on which her novella Made Up Of Arias is based, was a finalist for a Journey Prize anthology. Her fiction and non-fiction work has been widely published in major literary publications. She will be featured in a forthcoming documentary on the passengers, and the children of the passengers, of the Saturnia which will be featured on OMNI-TV. She is currently at work at a new novel entitled Vita’s Prospects.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

The House of Vacuity

This Vacant Paradise by Victoria Patterson (Counterpoint Press, 2011) 309 pages

I could complain that This Vacant Paradise (a reworking of Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth – one of my favourite books of all time) is nothing near the quality of the original. But that’s not fair. That’s an cheap target. It’s easy to trash books that dare to rework classics. I think, instead, I shall concentrate mostly on those elements which are different from the novel and how some of them are successful. Although I don't think I will be able to resist the odd snide remark ... A synopsis of the original and my thoughts about the House of Mirth is available here.

Our heroine Esther Wilson (Lily Bart in the original) is a daughter of privilege who has fallen on hard times in a haven of material excess and snobbery - Newport Beach, California in the Clinton era. Just to ensure that we know it is the Clinton era there are ample references to Hugh Lewis and the News, Vince Foster’s suicide and OJ's travails. These, I feel, are all unnecessary references and moves us away from the inherent drama of the plot which is powerful enough on it's own.

Esther is a disappointment to all around her and she can’t seem to summon up the necessary manipulation to snare a rich husband:

The circumstances are murky – it appears that the two were secretly fathered by Esther’s grandfather, grandmother Eileen's husband? Did I read that correctly? The passage is obscure, rendered in a flashback that Esther has. On Esther's mother's nightstand is a photo of the grandfather, the same one that sits on the grandmother's nightstand. Ohhhh, I see (I think) ...

Eric, who has become a homeless drug addict, is sensitively and poignantly portrayed – his acute suffering and alienation humanize the sometimes shallow Esther who desperately cares for him; this sets her apart from the grasping trophy wives who surround her in Orange County. She shares money, clothing, food with Eric. It redeems her - despite her petty thievery from the clothing store she works in, her vanity and shallow preoccupation with her looks, and, her diminished self esteem.

But why wouldn't Esther be obsessed with her looks - it is her only currency as a female without means, and it is a powerful one at that. She is a college dropout with an underdeveloped intellect, living with her vitriolic grandmother, and working in a clothing store part-time with no other means of support aside from her grandmother's sporadic and controlling largess.

Charlie Murphy, a slightly pretentious Orange County Community College professor (need I say more than those four words?) and the cerebral, left-leaning "black sheep" of a wealthy family, stands in for Lawrence Selden, Lily’s romantic interest. At times the novel devolves into a sort of cheesy chicklit romance novel. I know the book is set in the late 20th c. and not the early 20th c. but the focus on the sexual aspects of the relationship is disconcerting and, again, unnecessary to the plot.

We loved the book and the book's premise, we don't need to see all the gritty details of their physical relationship (at least I didn't). In the original, I did not see it as a relationship primarily of sexual attraction but more of two kindred souls who were drawn to each other in a repressive era that refused to accept their psychological differences from the values of a certain affluent strata of the Gilded Age.

May a man and woman be attracted to each other, care for each other, and not sleep together in a novel in this day and era? Apparently not …

I confess that Lawrence Selden is a favourite literary character of mine - to have him transformed into Charlie, the type of professor who dates and beds ex-students and is obsessed with Esther’s looks is disappointing. It’s not that his character has been changed, it’s that it feels utterly false to me and the book.

One criticism I read rang very true: “This Vacant Paradise valiantly aims at but sometimes misses, settling instead for repulsive personal details unconnected to its themes of money and class and their disfiguring—indeed crushing—effects on a certain type of female personality.”

The description of the decline of the grandmother Eileen is particularly vulgar and disturbing – Mrs. Julia Peniston (the woman who takes in Lily when her parents die and from whom she is expected to inherit) she is not. Eileen’s demise is ugly and unnecessarily graphic. Esther's interaction with Charlie and especially Jim Dunnels, a wealthy, older, predatory suitor who offers her some financial relief, is coarse and explicit at times but it did not have to be to be emotionally effective.

Although Wharton's anti-Semitism was overt and truly ugly she did colour the Simon Rosedale character in a more humane aspect in certain passages of the book (represented in this book by the super rich ex-NBA star Fred Smith - black is the new Jew here). Rosedale genuinely cares about Lily's fate and tries to help her when all of the friends in her circle have abandoned her; he loves, and is charmed by, children, an endearing quality. Despite the ugliness of the portrayal there is a glimmer of humanity beneath.

Fred Smith is a two dimensional black cartoon who is never really fleshed out - loving the display of wealth and bling, surrounded by "hot" women, arrogant and overbearing. How did Patterson develop the Smith character - by watching rap videos? Fred has a weakness for Esther but it appears to be more rooted in her physical beauty rather than in a appreciation of her character.

It is unnerving how every woman’s physical attributes are dissected, criticized and demeaned by all of the characters male and female (including, and especially, Esther) but, I fear, this is a very real component of that materialistic world where breast implants, plastic surgery and botox abound. That does ring true.

One thing pleases me about this novel. I don’t want to reveal the ending but I am grateful that in the late 20th c. it is not necessary to kill off the heroine who defies societal norms. She is diminished, she is broken but, luckily, she survives.

I see I have failed to keep the bitchy tone out of this review much as I have striven to be even-handed. Oh well, mess with my Lily and see what happens?

I could complain that This Vacant Paradise (a reworking of Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth – one of my favourite books of all time) is nothing near the quality of the original. But that’s not fair. That’s an cheap target. It’s easy to trash books that dare to rework classics. I think, instead, I shall concentrate mostly on those elements which are different from the novel and how some of them are successful. Although I don't think I will be able to resist the odd snide remark ... A synopsis of the original and my thoughts about the House of Mirth is available here.

Our heroine Esther Wilson (Lily Bart in the original) is a daughter of privilege who has fallen on hard times in a haven of material excess and snobbery - Newport Beach, California in the Clinton era. Just to ensure that we know it is the Clinton era there are ample references to Hugh Lewis and the News, Vince Foster’s suicide and OJ's travails. These, I feel, are all unnecessary references and moves us away from the inherent drama of the plot which is powerful enough on it's own.

Esther is a disappointment to all around her and she can’t seem to summon up the necessary manipulation to snare a rich husband:

She needed to look out for herself, before it was too late, since no one else would. Yet she couldn’t follow through, . . . as if a leaden weight inside her kept her at the couch — when she should be impressing potential husbands with her sad beauty.Her father, a closeted homosexual, was disowned by the family – died young and in impoverished circumstances. In House of Mirth, Lily's father has a series of financial setbacks and succumbs to illness because of them leaving the family impoverished. Interestingly enough, Esther and her brother Eric (a character who did not exist in the original book) come from some very frightening circumstances where, at a barely cognizant age, they witness their biological mother O.D. and are eventually adopted by their father.

The circumstances are murky – it appears that the two were secretly fathered by Esther’s grandfather, grandmother Eileen's husband? Did I read that correctly? The passage is obscure, rendered in a flashback that Esther has. On Esther's mother's nightstand is a photo of the grandfather, the same one that sits on the grandmother's nightstand. Ohhhh, I see (I think) ...

Eric, who has become a homeless drug addict, is sensitively and poignantly portrayed – his acute suffering and alienation humanize the sometimes shallow Esther who desperately cares for him; this sets her apart from the grasping trophy wives who surround her in Orange County. She shares money, clothing, food with Eric. It redeems her - despite her petty thievery from the clothing store she works in, her vanity and shallow preoccupation with her looks, and, her diminished self esteem.

But why wouldn't Esther be obsessed with her looks - it is her only currency as a female without means, and it is a powerful one at that. She is a college dropout with an underdeveloped intellect, living with her vitriolic grandmother, and working in a clothing store part-time with no other means of support aside from her grandmother's sporadic and controlling largess.

Charlie Murphy, a slightly pretentious Orange County Community College professor (need I say more than those four words?) and the cerebral, left-leaning "black sheep" of a wealthy family, stands in for Lawrence Selden, Lily’s romantic interest. At times the novel devolves into a sort of cheesy chicklit romance novel. I know the book is set in the late 20th c. and not the early 20th c. but the focus on the sexual aspects of the relationship is disconcerting and, again, unnecessary to the plot.

We loved the book and the book's premise, we don't need to see all the gritty details of their physical relationship (at least I didn't). In the original, I did not see it as a relationship primarily of sexual attraction but more of two kindred souls who were drawn to each other in a repressive era that refused to accept their psychological differences from the values of a certain affluent strata of the Gilded Age.

May a man and woman be attracted to each other, care for each other, and not sleep together in a novel in this day and era? Apparently not …

I confess that Lawrence Selden is a favourite literary character of mine - to have him transformed into Charlie, the type of professor who dates and beds ex-students and is obsessed with Esther’s looks is disappointing. It’s not that his character has been changed, it’s that it feels utterly false to me and the book.

One criticism I read rang very true: “This Vacant Paradise valiantly aims at but sometimes misses, settling instead for repulsive personal details unconnected to its themes of money and class and their disfiguring—indeed crushing—effects on a certain type of female personality.”

The description of the decline of the grandmother Eileen is particularly vulgar and disturbing – Mrs. Julia Peniston (the woman who takes in Lily when her parents die and from whom she is expected to inherit) she is not. Eileen’s demise is ugly and unnecessarily graphic. Esther's interaction with Charlie and especially Jim Dunnels, a wealthy, older, predatory suitor who offers her some financial relief, is coarse and explicit at times but it did not have to be to be emotionally effective.

Although Wharton's anti-Semitism was overt and truly ugly she did colour the Simon Rosedale character in a more humane aspect in certain passages of the book (represented in this book by the super rich ex-NBA star Fred Smith - black is the new Jew here). Rosedale genuinely cares about Lily's fate and tries to help her when all of the friends in her circle have abandoned her; he loves, and is charmed by, children, an endearing quality. Despite the ugliness of the portrayal there is a glimmer of humanity beneath.

Fred Smith is a two dimensional black cartoon who is never really fleshed out - loving the display of wealth and bling, surrounded by "hot" women, arrogant and overbearing. How did Patterson develop the Smith character - by watching rap videos? Fred has a weakness for Esther but it appears to be more rooted in her physical beauty rather than in a appreciation of her character.

It is unnerving how every woman’s physical attributes are dissected, criticized and demeaned by all of the characters male and female (including, and especially, Esther) but, I fear, this is a very real component of that materialistic world where breast implants, plastic surgery and botox abound. That does ring true.

One thing pleases me about this novel. I don’t want to reveal the ending but I am grateful that in the late 20th c. it is not necessary to kill off the heroine who defies societal norms. She is diminished, she is broken but, luckily, she survives.

I see I have failed to keep the bitchy tone out of this review much as I have striven to be even-handed. Oh well, mess with my Lily and see what happens?

Thursday, April 14, 2011

Launch of Sweet Lemons 2

Launch of the anthology Sweet Lemons 2:

International Writings with a Sicilian Accent

edited by Venera Fazio and Delia DeSantis

International Writings with a Sicilian Accent

edited by Venera Fazio and Delia DeSantis

Thursday April 14, 2011

7.30p

Annex Live

296 Brunswick Ave.

(south of Bloor)

Featuring poetry and prose by:

John Calabro, Domenic Capilongo,

Giovanna Capozzi, Delia De Santis, Bruna Di Giuseppe-Bertoni,

Desi Di Nardo, Venera Fazio, Isabella Katz, Darlene Madott,

Desi Di Nardo, Venera Fazio, Isabella Katz, Darlene Madott,

Maria Scala and Michelle Alfano as emcee

John Calabro’s first novella, Bellecour, was published in 2005 by Guernica. LyricalMyrical published Calabro’s chapbook of short stories, Somewhere Else, in 2006. His short stories, essays and reviews have appeared in many journals. The Cousin his second novella was published in 2009 by Quattro Books. John Calabro is now president and publisher of Quattro Books and is working on another novella, The Innocence of an Imperfect Man, as well as a book of non-fiction on the novella.

Domenico Capilongo is a high school teacher from Toronto, ON. His first poetry collection, I thought elvis was italian, was published in 2008. His poetry has appeared in many literary magazines and he was short-listed for the gritLIT 2009 Poetry Contest. Quattro Books published hold the note, his new jazz-inspired collection, in 2010.

Giovanna M.R. Capozzi: 36 years old and a proud Italo-Canadian. I am an immigrant’s daughter who shares their story. I am the voice of Autism through my brother’s challenges. I am an educator who teaches reality with sweet and sour sarcasm. I am a wife who believes in commitment and vital compromise. I am a mother, taking all the qualities above to raise my sons, accepting that I will falter in the name of maternal instinct. I am a writer that takes all these roles and expresses the beautiful intricacies that come with them.

Delia De Santis’ short stories have appeared in literary magazines in Canada, United States, England, and Italy, and in several anthologies. She is co-editor of the anthologies Sweet Lemons (Legas, 2004), Writing Beyond History (Cusmano, 2006), Strange PeregrinationsSweet Lemons 2 (Legas, 2010). She is the author of the collection Fast Forward and Other Stories (Longbridge Books, 2008). (Frank Iacobucci Centre for Italian Canadian Studies, 2007).

Bruna Di Giuseppe-Bertoni was born in Italy and immigrated with her family to Canada in 1964. Her passions are painting and writing and she has won a number of literary awards for her poetry. She has published in Italian, the poetry collection Sentieri D'Italia. Her writing appears in a number of anthologies, including Writing Beyond History and Reflections on Culture.

Desi Di Nardo is the author of two books, The Plural of Some Things, and most recently, The Cure Is a Forest. Her work has been published in many Canadian and international journals and anthologies, performed at the National Arts Centre, featured on Toronto's transit system, and displayed in the Official Residences of Canada. She has worked as a writer-in-residence, literacy facilitator, and English professor. www.desidinardo.com

Venera Fazio was born in Sicily and now lives in Bright’s Grove, ON. She is co-editor of the anthologies Sweet Lemons: Writings with a Sicilian Accent (2004), Writing Beyond History (2006), Strange Peregrinations: Italian Canadian Literary Landscapes (2007) and Reflections on Culture: An Anthology of Creative and Critical Writing (2010). Her poetry and prose have appeared in literary magazines in Canada, the United Sates and Italy.

Isabella Colalillo Katz is a poet, writer, editor, translator and educator. She is the author of two books of poetry, Tasting Fire (Guernica, l999), And Light Remains (Guernica, 2006) and a new book exploring creativity, titled Awakening Creativity and Spiritual Intelligence (LAP, 2009). Her creative work appears in numerous journals and anthologies.

Darlene Madott is a lawyer and writer. Her publications include Joy, Joy, Why Do I Sing? (Women’s Press/Canadian Scholar’s Press, 2004), of which “Vivi’s Florentine Scarf” won the Paolucci Prize of the Italian-American Writers’ Association. The title story of Making Olives and Other Family Secrets (Longbridge Books, 2008) won the F.G. Bressani Literary Prize.

Maria Scala is a writer and editor living in Toronto with her husband, daughter, and son. Her poetry and non-fiction have appeared in various Canadian and international publications including More Sweet Lemons: Writing with a Sicilian Accent (Legas), Descant, Thunderclap! Magazine, mamazine.com, literarymama.com, PoetryReviews.ca, and Página/12. Between O and V, her poetry chapbook, was published in 2008 by Friday Circle (University of Ottawa.) Maria has poems forthcoming in Descant: Sicily, and French translations of her poems by Filippo Salvatore will appear in L'arbre à paroles: les deux Siciles. Her blog, "August Avenue", is found at mariascala.blogspot.com

And as emcee...

Michelle Alfano is a co-organizer of the (Not So) Nice Italian Girls & Friends Reading Series and a Co-Editor with Descant. Her novella Made Up of Arias (Blaurock Press) won the 2010 Bressani Prize for Short Fiction. Her short story “Opera”was a finalist for a Journey Prize anthology. She will be featured in a forthcoming documentary on the passengers, and the children of the passengers, of the Saturnia that will be featured on OMNI-TV. She is currently at work at a new novel entitled Vita’s Prospects.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

What you get away with

|

| You say art, some say...what? |

It got me wondering if something may be defined as art if the viewer does not comprehend the elements of the piece that are presented to them. Is there art without comprehension? Isn’t art predicated on successful communication to the spectator?

Two definitions of art are “the products of human creativity” and “the creation of beautiful or significant things”. Neither definition includes the precondition that it must be perceived by the viewer as such. It is a relatively modern idea that anything may be art. Do we all buy into the theory that “if an artist decides that an object is art and it’s placed in an art space, then that object is art.” Another related school of thought might be the more cynical Andy Warhol aphorism that, “Art is what you get away with.”

The Dadaist Marcel Duchamp famously submitted his work “Fountain”, a urinal shown above, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibit in 1917. The work was rejected as art; Duchamp resigned from the society in protest. Duchamp acknowledged that, “The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

What if I am neither able to decipher nor interpret … does that lessen or weaken the artistic nature of the work? I would suggest no with just a trifle hesitation. Many works that are initially seen as transgressive, avant-garde and, perhaps, lacking in value, sometimes increase their ability to captivate, communicate and engage (such the Impressionist, Surrealist and Dadaist movements) with the passage of time.

In the mid 19th c. historical figures and scenes, religious themes, and portraits were considered objects worthy of artistic representation while landscape and still lifes were not. Colours were somber. The Impressionists of the 1860s defied the rules of academic painting using “short, broken brush strokes of pure and unmixed color”. They took the physical process of painting out of the studio and into the outdoors with bright, vivid colours and “unconventional” subjects. Impressionism, which was initially received in a hostile manner, may now be perceived as a gentle, universally revered, bourgeois art form of the 21st century.

Is it merely that progressive art + time = classic? I readily admit that I may not be clever enough to recognize that a piece is a work of art yet I think will reserve the right to withhold that description for work merely because I am told it is.

Originally posted in an altered version on descant.ca/blog.

Originally posted in an altered version on descant.ca/blog.

Friday, April 1, 2011

As much soul as you

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (First published in 1847) 477 pages

In a writing course that I once took the instructor advised us: every writer has an agenda or a moral that they want to impart in their fiction. Bronte, it seemed, dared to suggest that you can be plain, little, vilified and scorned by many and still triumph as the heroine of the narrative.

Jane’s trials and tribulations rend the heart particularly as she falls into well-loved (and well-worn) tropes: Orphaned child. Woman in Jeopardy. Woman of Independence. Dutiful wife.

Jane, The Orphan

Jane is brave, resilient, and has a strong morale code. She is, by her own admission, plain and little and we love her all the more for it. When we first meet Jane she is living as the ward of a despised aunt, a Mrs. Reed, the wife of her mother’s brother at Gateshead. Her parents, both dead of an illness when she was an infant, leave Jane orphaned and under the care of her uncle Mr. Reed. When her uncle dies, Jane is at the mercy of an unfeeling and vicious aunt who despises Jane for her poverty and what the aunt perceives as her lack of admirable attributes: beauty, obedience, a docile nature - a Victorian ideal of the female child.

For make no mistake, Jane is not docile, nor beautiful, nor obedient. She is physically attacked, in the opening chapter, by her cousin John, and strikes back, blow for blow, for which she is punished severely by being locked in the dreaded Red Room where her uncle both died and where his corpse was laid out. This is particularly horrific for the ten year old as she and the rest of the household have a superstitious dread of the room fed by the tales of the supernatural by servants (a familiar occurrence in the Bronte household where Charlotte grew up - which contained both future authors Emily (Wuthering Heights) and Anne (Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall).

Her fright is so severe that she suffers a sort of fit and falls into unconsciousness. A kindly doctor summoned to nurse her quickly ascertains that Jane is unwelcome in the house and deeply unhappy so it is suggested that she be enrolled at the Lowood Institution for orphaned and destitute girls.

Here is a new sort of hero. Plucky Jane, defiant to the last, unnerves her aunt by proclaiming before she leaves that she will tell all how she was treated by her aunt and will never ever profess to be grateful to her.

Lowood proves, in different ways, as harsh and challenging as the Reed household. Poor and inadequate amounts of food, strict enforcement of rules of self-abnegation, clumsily made clothes and inadequate shoes in harsh, inclement weather ... the girls are forced to trudge back and forth long distances through bad winter weather to church for services. Here Bronte attacks the forces of Evangelicalism which swept through England and condemned the poor to unhappy and unhealthy circumstances for the sake of their souls. These elements vanquish many of the girls.

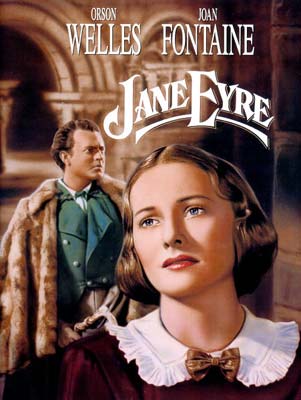

|

| Joan Fontaine - perhaps long in the tooth for the role, at 27, but capturing the essenceof our heroine in the 1944 classic |

Jane remains at LowoodThornfield estate where she meets her destiny in the person of Mr. Rochester.

Jane, The Woman in Jeopardy

Jane is hired to tutor a young student from France – the result of Rochester's brief liaison in France? He denies that Adele Varens is his child. For many months, Jane does not meet the mysterious Mr. Rochester who owns the estate. But she is troubled by a mysterious laugh she hears from the upper reaches of the mansion. She is told by the kindly housekeeper Mrs. Alice Fairfax that it is only Grace Poole, a surly-faced servant who only interacts intermittently with the rest of the staff. But the tone is set. Jane feels unnerved by the ominous laugh and cannot reconcile it with the servant's grim countenance when she encounters her.

A series of frightening events ensue...someone (Jane presumes it is the ominous servant Grace Poole) starts a fire in Rochester's room. She saves Rochester from burning to death in his own bed and Rochester insists on concealing the information from the rest of the household. Overnight, Richard Mason, a guest at the house, is attacked, his arm and flesh appear to be torn apart by teeth and he has been stabbed. He is nursed by Jane and whisked out of the house before the other guests can determine what has happened. Jane begins to feel that she is trapped in the house with a volatile, violent creature who has the forbearance of her master and she can't understand why this should be so.

Rochester courts a local beauty, a Blanche Ingram, bringing her to the house with a gay party of the very rich and distinguished. She is on the lookout for a rich husband and does her best to entice Rochester. Jane particularly dislikes her particularly because of the demeaning manner in which she treats both Jane and Adele.

The courtship of Miss Ingram is interrupted by news that Jane must attend to her Aunt Reed who is dying and has requested Jane's presence at Gateshead. Before she leaves she extracts a promise from Rochester that when he marries Miss Ingram Jane will be placed in a position close to Thornfield, close to him.

|

| Charlotte Gainsborough as Jane in Zeffirelli's 1996 version ... |

The aunt, as supercilious and as disdainful in her death as she was in life, informs Jane that she has withheld an important secret from her. Three years prior, Jane's uncle John Eyre, her father's brother, had contacted the Reeds to inquire as to Jane's whereabouts. Mrs. Reed confesses that she told the uncle that Jane had died of typhus at Lowood because she did not want Jane to inherit her uncle's wealth.

Jane encounters her old enemies, her Reed cousins - Georgiana, the dissipated beauty, and her sister Eliza, the mean spirited, acid tongued religious zealot - who loath both Jane and each other and are determined to separate once their mother has died (they do - one to glittering London to marry well and the other to a nunnery in France). They seem to represent two unpleasant extremes - the vacant society beauty who cares for no one and nothing but herself and the bitter, unsociable "old maid" who wraps herself in the garb of a devout Christian the better with which to spew disdain on other mere mortals.

Jane encounters her old enemies, her Reed cousins - Georgiana, the dissipated beauty, and her sister Eliza, the mean spirited, acid tongued religious zealot - who loath both Jane and each other and are determined to separate once their mother has died (they do - one to glittering London to marry well and the other to a nunnery in France). They seem to represent two unpleasant extremes - the vacant society beauty who cares for no one and nothing but herself and the bitter, unsociable "old maid" who wraps herself in the garb of a devout Christian the better with which to spew disdain on other mere mortals.

Jane returns to Thornfield Hall in a daze with the news that she is likely to inherit her rich uncle's estate in Madeira. She daily anticipates news of Mr. Rochester's engagement. She hears none. She is then informed by Rochester that he wishes her to relocate once he is married, to Ireland, to serve as a governess to five children. This prevarication is more than she can bear.

She struggles with the bitter news that Rochester intends to marry but then to be separated from him by such a great distance! When Jane reluctantly agrees to the necessity of her leaving Thornfield, Rochester baits her a bit with the question as to why she must leave. This elicits one of Jane's greatest speeches and catapults her into the category of one of 19th c. English literature's greatest heroines:

Do you think I can stay to become nothing to you?...Do you think because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? - You think wrong - I have as much soul as you, - and full as much heart! And if God gifted me with some beauty, and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you.

Bronte was absolutely determined to prove that a plain, unassuming girl with no fortune could be as captivating on the page as greater, more flamboyant beauties. She succeeds beautifully.

It is then that Rochester reveals his true intentions: the presence of Miss Ingram was but a ruse to incite Jane's jealousy. Rochester wants to marry Jane, soon, within a month. But Jane's ominous dreams of trying to comfort a wailing child offer a premonition of the events to come. This is also accompanied by visions of Thornfield in ruins. But the dream doesn't end there...a presence enters Jane's room the night before the wedding, takes her wedding veil, surveys herself in it in the mirror and tears it apart and flings it to the ground.

The next day, the "madwoman in the attic" is revealed to all and suffice it to say that the marriage does not take place. Rochester's secret is revealed - in one of those melodramatic, impossible coincidences that mar this work. Aside from the element of horror introduced here with the appearance of Bertha, the lunatic, feral wife who resides in the attic, there are the sad circumstances of her family history. There is a suggestion that part of it might be attributed to her Creole background. This could easily necessitate a whole other essay on its own. The vitriol that Rochester hurls at Bertha and her family withers away the esteem I have for the character of Rochester. This of course is not Bronte's intention. His anguished explanation to Jane is meant to explain his futile attempt to conceal his first marriage and absolve him of being perceived as an evil, conniving philanderer. Still the ugliness of his response makes one flinch.

The next day, the "madwoman in the attic" is revealed to all and suffice it to say that the marriage does not take place. Rochester's secret is revealed - in one of those melodramatic, impossible coincidences that mar this work. Aside from the element of horror introduced here with the appearance of Bertha, the lunatic, feral wife who resides in the attic, there are the sad circumstances of her family history. There is a suggestion that part of it might be attributed to her Creole background. This could easily necessitate a whole other essay on its own. The vitriol that Rochester hurls at Bertha and her family withers away the esteem I have for the character of Rochester. This of course is not Bronte's intention. His anguished explanation to Jane is meant to explain his futile attempt to conceal his first marriage and absolve him of being perceived as an evil, conniving philanderer. Still the ugliness of his response makes one flinch.

Jane, The Woman of Independence

Jane flees, after an interminable length of time in which Rochester attempts to justify his bigamist intentions and vilifies his mentally ill wife. Foolishly and inexplicably, Jane leaves with very little money - even though we know that she has just become aware of a rich relation who means to leave her money and could very likely fund her escape from Thornfield in a more hospitable manner.

Here, three quarters into the book, the plot falters for me. Jane ends up destitute, starving, thoroughly rain-soaked on the doorstep of, lo and behold, her paternal cousins - St. John, Diana and Mary Rivers. But they do not learn of this connection for many months. When it is discovered that Jane has inherited a great deal of money from their mutual relative (the three cousins have been excluded from the will), Jane generously shares this with her cousins. But her cousin St. John has other plans for Jane.

He wishes to marry her but not out of love - so that she may accompany him to India to work as a missionary. This she refuses but not because she does not wish to be a missionary. She refuses because it would be a loveless marriage with a cold, unforgiving man whom she feels would destroy her emotionally.

Jane is determined to spend a peaceful life with her female cousins in their cozy cottage, now that all have sufficient means to live. But she is haunted by a fitful dream in which she hears Rochester's voice calling her name and offering a foreboding sense that all is not well at Thornfield.

She makes her trip back to Thornfield and as she approaches the Hall hears a story which justifies all her anxieties about Rochester's fate. Bertha has burnt down Thornfield Hall, totally demolishing the mansion. Rochester, whilst trying to save the residents of the Hall, was both blinded and had his hand crushed which subsequently had to be amputated. He is to be found in a little cottage near the Hall living with only two servants. Bertha has flung herself to her death.

Jane, The Dutiful Wife

Jane's appearance strikes Rochester as an apparition - much like the ones where he has imagined her return many times before. Reader, yes, she has made her decision, she will stay and marry Rochester whom she likens to a blinded lion - to love and sustain Rochester in his now diminished state, despite his flaws, despite his frailties. She may leave if she wants to - she is rich, she is independent. She may remove herself from what may prove to be a difficult relationship. But she does not. And that's why we love Jane so.

|

| The latest incarnation of Jane, Mia Wasikowska, in the 2011 film... |

Some of the many faces of Jane Eyre:

Film (2011) with Mia Wasikowska and Michael Fassbender

TV Mini-series (2006) with Ruth Wilson and Toby Stephens

TV (1997) with Samantha Morton and Ciaran Hinds

Film (1996) with Charlotte Gainsbourg and William Hurt

BBC Mini-Series (1983) with Zelah Clark and Timothy Dalton

TV (1973) with Sorcha Cusack and Michael Jayston

Film (1970) with Susannah York and George C. Scott

TV Series (1956) with Daphne Slater and Stanley Baker

TV Series (1956) with Daphne Slater and Stanley Baker

Film (1944) - the gold standard - with Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles

There are film versions going back to 1910.

There are film versions going back to 1910.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)