I bow down before the master Flaubert...I had been thinking of Emma Bovary and her creator for some time now, thinking I should revisit the book. Fortuitously, last year, I was excited to learn of this new translation which was creating a great buzz in the literary world.

Flaubert was, perhaps, a scoundrel, a womanizer, a Mama’s boy, but, oh, how he understood the torment of forbidden desire, the rituals of love.

In the introduction, the translator Lydia Davis describes the book as depicting "the lives of its characters objectively, without idealizing, without romanticizing, and without intent to instruct or to draw a moral lesson". Flaubert's work was soon labeled "realist fiction", a description he disliked. His work was considered immoral by some, coarse and vulgar. He was even briefly taken to court on charges that the book was immoral. Certainly it was shocking.

This is a heart that understands passion. And lust. And greed. And many other emotions which may have frightened the bourgeois in the 1850s that Flaubert so despised and mocked in this novel.

Convent educated Emma Rouault is courted by Dr. Charles Bovary who has fallen in love with her, while treating her father, a prosperous farmer, for his broken leg. Well before he becomes a widower, he becomes entranced with Emma. Her black hair and pretty face, her delicate ways, her elegant, simple style. Bovary, saddled with an imperious older wife whose cold feet in the marital bed (what a perfect description of his distaste) repel him is easily tempted by Emma.

The detail is so sensuous and the language so carefully constructed here. It makes my heart flutter just to read of Charles' admiration for Emma under her pretty parasol before he asks her to marry him or Emma blowing flower petals to her husband as he rides away during the honeymoon period of their marriage…

Emma, who had been cosseted in a convent and raised on Walter Scott epics, has grand romantic dreams. She pines for her knight to ride up to the manor and take her away. Before she marries, she believes that what she lacks is a husband and married love. After she marries, she dreams of romance, wealth, and adventures that never transpire.

She considers her husband Charles to be coarse and foolish. He is admired for his decency and gentleness by all except Emma. But Charles desires only Emma: “The universe, for him, did not extend beyond the silly contour of her undershirt…” Charles who cannot follow the plot of Lucia di Lammermoor because the music distracts him from the recitatives.

An invitation to the home of the Marquis d’Andervilles (rewarding the good doctor for a medical service) only further inflames Emma’s passions. Emma is dazzled by the ladies’ gowns, the exquisite food, and the opulence of his chateau, the people whom she deems cultured, rich and elegantly mannered. A waltz, still considered a bit risqué for the time, with the Marquis, sends her into a swoon. Why should she, better dressed, prettier, more refined, not be able to share in all the riches that life has to offer?

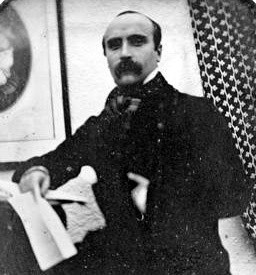

|

| A dashing Flaubert in his youth |

She becomes bored and excitable, yearning for more. “She wanted both to die and to live in Paris”. Her actions become inexplicable. She loses her taste for elegance and has fits of rage against the servants. She becomes slovenly. This chapter ends unexpectedly. We begin to suspect that Emma is perhaps slipping into madness. We soon learn, instead, that Emma is pregnant. Perhaps, the reader suspects, her anxieties are hormonal, not psychological.

Whenever I read this section I amazed how Flaubert has captured the desperation of the lonely housewife who feels herself to be cut off from the things she craves, the things she desires. She is the original desperate housewife. How did he access her desires - this spoiled, arrogant, misogynistic man of the world?

"I am in their skin," Flaubert said candidly and he sometimes found himself weeping while writing the novel. And it is quite engaging how fully he inhabits the fictional Emma’s mind.

Emma bears a daughter whom she names Berthe and whom she quickly farms out to a wet nurse in the country (a not uncommon occurrence for a woman of Emma’s class). Charles’ mother acidly asserts that Emma reads too many novels and isn’t occupied with enough work. Charles tiptoes around Emma thinking her too delicate, too fine at times, for her life as a doctor’s wife. He seeks a change for Emma and himself. They move to Yonville (a fictitious town) and he takes up the practice of a doctor who has just passed away in the area.

|

| Jennifer Jones as Madame Bovary (1949) |

But soon a new love interest is on the horizon…Rodolphe Boulanger, an aristocrat with a wandering eye and unscrupulous morals, who has decided to seduce Emma just for the fun of it. Bored, resentful, ambitious, she is ripe for the picking...How artfully Flaubert juxtaposes Rodolphe's honeyed whispered seduction of Emma with the declaration of the prizes awarded at the Agricultural Fair for the best manure!

Ensnared by her love of luxury, Emma becomes indebted to Lheureux, the dry good merchant, who soon determines Emma's secret when he threatens to take back an unpaid for riding crop. Emma can't pay for the articles that she has purchased on credit from Lheureux. Her alarm suggests to Lheureux that the riding crop is not for Charles but some unknown lover (he is correct).

Unfortunately for Charles he becomes convinced by the local provincials that he must try and assist young Hippolyte, a stable boy with a club foot. His experiments on the boy prove disastrous and the boy must eventually have his foot and calf amputated after much suffering. This tragedy only furthers Emma's disdain for Charles. "Everything about him irritated her now..." as everything in his, and her life, is refracted through the prism of Emma's unhappiness.

Hippolyte's tragedy had, at first, seemed a strange inclusion in Emma's narrative, the first few times I read it especially as it is juxtaposed between Emma's relationship with Rodolphe and the return of Leon to Emma's life. But it seems an apt metaphor upon further reading. The medical procedure on the boy seems the solution to a difficult situation (as does the affair with Rodolphe for Emma) but the experiment then leads to greater catastrophe and eventual disaster for the boy in the same way that the relationship with Rodolphe leads to entanglement with Leon and even more dire circumstances for Emma.

Rodolphe inevitably disappoints Emma to whom he has promised a life abroad with her child. He is so snake-like in casting her off that the reader immediately empathizes with the deluded Emma even though she has behaved shamefully towards Charles. Emma briefly contemplates suicide when she read Rodolphe's letter, collapses and lapses into a brain fever which lasts for some months nursed by the faithful Charles.

|

| Isabelle Huppert as Madame Bovary (1991) |

A neighbour begins to extol the virtues of music and theatre to Charles so he feels compelled to bring Emma to a production of Lucia di Lammermoor in Rouen. Quite by accident they encounter Leon who is completing his law studies and joins them in their booth. Now emboldened by his success with the local grisettes, he is determined to seduce Emma.

He hits upon a perfect ruse. When he mentions that an acclaimed singer will be performing the next night Charles insists that Emma remain in Rouen to hear him although Charles must leave that very night.

Leon calls upon Emma at her hotel the next day and professes his love. She demurs but promises that they will meet the next day at the Cathedral. She composes a letter that night telling him why they must desist from meeting but decides to hand him the note in person the next day.

At the Cathedral, the verger tries to tempt Emma and Leon with the beauties and history of the church while Leon attempts to lure Emma away. Emma's feigned interest in religious faith (represented by the visit to the Cathedral) collides with Leon's more corporeal desires. In frustration, he hurriedly calls for a cab while she tepidly resists.

Here ensues, in my estimation, the most erotic passage in modern Western literature (Part III, Chapter 1 - see for yourself!). Leon pulls Emma into the cab and urges the rider on, anywhere as long as they move. We see nothing of what happens in the covered coach. The cab drives on and on through Rouen and whenever the driver slows down we only hear Leon's voice, cursing the driver and compelling him onward attracting the attention of curious onlookers. The driver beats the horses onwards mercilessly. At the end of the ride, the only thing we see of Emma is:

...a bared hand passed beneath the small blinds of yellow canvas, and threw out some scraps of paper that scattered in the wind, and farther off lighted like white butterflies on a field of red clover all in bloom.When Emma returns to Yonville we are introduced to two disturbing incidents both signaling ominous future events. Emma's father-in-law has died during her absence and when she searches for Charles at the pharmacist's we find Homais reprimanding his assistant for innocently being in contact with a jar of arsenic in the pharmacy. Both seemingly innocuous events hint at more ominous events to come.

Leon and Emma begin a series of trysts in Rouen - the air is filled with the smell of "absinthe, cigars and oysters" - where Emma goes under the pretext of getting piano lessons which Charles encourages. She disappears for two or three days at a time. Their meetings are passionate and intense. Emma becomes for Leon "the beloved of every novel, the heroine of every drama, the vague she of every volume of poetry".

But eventually she tires of Leon and he tires of Emma. Once when he disappoints Emma, tarrying with a surprise visit by Monsieur Homais, she comes to the realization that she no longer loves him as she once did. Their relationship has become as pedestrian as any marriage might be. Here Flaubert warns the reader, "We should not touch our idols; their gilding will remain on our hands."

Once, returning from a rendezvous, Emma encounters a beggar swathed in rags, whose bloodied, empty eye sockets ooze pus. To her horror, the man clings to her coach begging for money and singing. For me, this horrifying sight presages the hideous dwarf who appears in the unfortunate Anna's dream in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (1873) almost twenty years later.

Emma continues to rack up ruinous debts with Lheureux, the dry good merchant, which Charles has no knowledge of while Leon attempts to distance himself from Emma at the urging of his mother and employer.

When Emma is finally compelled by the bailiff to pay her debt of 8,000 francs or risk seizure of all of their possessions, she frantically searches for financial assistance and even, in desperation, approaches Rodolphe who cannot or will not assist her.

In a frenzy, she runs to the pharmacist's abode then seizes and swallows some arsenic. Her final days are painful and graphically portrayed. Flaubert so identified with Emma during her last days that he often found himself to be physically ill. Emma's slow demise exhibits all the contradictions of her troubled nature: sudden religious fervor (passionately kissing the crucifix that she demands be brought to her), lingering vanity (a request to see herself in a hand mirror), guilt and shame at her past actions as if she is expecting some sort of retribution (represented by her horror at hearing the voice of the blind beggar singing through the window)...

Flaubert is not above delivering a blow to the reader's tender sensibilities as he or she is lulled into a gentle image of Emma's final visage before burial. As she is dressed in white for her funeral the women who are dressing her comment on how beautiful she looks, how life-like. The corpse's mouth suddenly leaks a black vomit nearly destroying the beatific image presented. It's as if Flaubert is saying, "Do not be fooled by her beauty, do not romanticize her; here lies a truly desperate and ugly creature."

Charles falls to ruin, at first emulating his wife's exorbitant habits then allowing himself to dissipate when he finds Emma's secret letters from Rodolphe and Leon. Everyone around Charles prospers as if to mock him for his goodness. His practice is ruined and his patients neglected, servants desert him, Berthe runs about in torn clothes, his debts overwhelm him.

Rodolphe, although uneasy in his suspicions that Charles knows, is impervious to troubles. Leon marries well. Felicité, Emma's servant, runs off with most of Emma's wardrobe. Lheureux seizes most of Charles' possessions because of the debt. The pharmacist Monsieur Homais, the inadvertent purveyor of Emma's death by arsenic, receives his much desired Legion of Honor. When Charles dies, his daughter Berthe is sent to live with a distant aunt who, as she is poor, must send the girl to work in a cotton mill.

I am uncertain that there is no moral tone here. It is quite clear that Emma's infidelity has lead to death and ruination for the family.

If this was not Flaubert's prescription for preserving one's fidelity, I don't know what is. It's as if he is mocking us...the bourgeois, the hypocritical, the devious, the morally bankrupt, all triumph except for Emma (and Charles) who must pay the price for all of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment